Amy Cuddy is Associate Professor of Business Administration in the Negotiation, Organizations & Markets Unit at Harvard Business School. As a social psychologist she is known for work on stereotyping, discrimination, emotions, power dynamics, nonverbal communication, and the effects of social stimuli on hormone levels. This article is based on her TEDx talk at TEDGlobal 2012 in Edinburgh, which has received over 16 million views.

We’re fascinated by peoples’ body language. But can our body language change how we feel about ourselves?

Awkward interactions to a smile or a contemptuous glance or a wink can have us talking for weeks.

When we think about non-verbal communication, we have to ask – what exactly is being communicated?

Social scientists have spent a lot of time looking at the effects of our body language on judgements. We make sweeping judgements and inferences from body language.

These judgements can predict very meaningful life outcomes such as who we are, who we hire or promote and who we ask out on a date.

Example Judgment #1

Nalini Ambady, Tufts University

When people watch 30 second soundless clips of physician/patient interactions, their judgements of the physician’s niceness predict whether or not that person will be sued. This means it is less about their competence but about whether we like that person and how they interacted.

Example Judgement #2

By Alex Todorov, Princeton

Judgements of political candidates faces in one second predict 70% of US senate and googonotorial outcomes.

Digital Example Judgement

Emoticons used well in online negotiations can lead you to claim more value from those negotiations.

The amazing idea of power dynamics

When we think of nonverbal communication we think of how we judge others, how they judge us and what the outcomes are. We tend to forget the other audience influenced by our nonverbal communication, thoughts, feelings and physiology – and that’s ourselves.

A particularly interesting area here is power dynamics, in non-verbal expressions of power and dominance.

What are these?

In the animal kingdom they are about expanding, making yourself big, stretching out, taking up space. It’s about opening up. This is true across the animal kingdom, not just limited to primates. Animals do this when they are powerful chronically but also when they feel powerful in the moment.

Jessica Tracey has studied pride and has shown that people who are born with sight AND those born congenitally blind throw their hands in the air and expand their bodies when they win a competition – people do the same when they cross the finish line whether they have or haven’t seen anyone strike a winning pose before.

When we feel powerless, we close up, we wrap ourselves up, we make ourselves smaller, we don’t want to bump into the person next to us. Animals and humans do the same thing.

When it comes to power, we tend to complement the others’ non verbals. So if someone’s being very powerful with us, we tend to make ourselves smaller – we don’t mirror, we do the opposite.

Power dynamics in the classroom

I’m watching behaviour in the classroom, and I notice that MBA students exhibit a range of non-verbals. Some show the characteristics of alphas – they come into the room, right into the middle, before class starts. They want to occupy space, so when they sit down they spread out.

Other people are virtually collapsing when they come in – they sit down and make themselves tiny.

This is related to the extent to which the students participate and how well they participate – this is very important in an MBA classroom because participation counts towards half the grade.

This is also extremely related to gender. Women are more likely to make themselves smaller than men because they feel chronically less powerful than men, so it’s not surprising.

The other thing is that business schools have struggled with gender grade gap. These people are equally qualified but there is a difference in grades between men and women, directly attributable to participation.

This made me wonder: is it possible we could get people to fake power poses and would this lead them to participate more?

Can you fake it until you make it?

We know our nonverbal communications govern how other people think and feel about us. Do our nonverbal govern how we think and feel about ourselves?

Some evidence they do. We smile when we feel happy but when we’re forced to smile by holding a pen between our teeth it makes us feel happier too.

When you feel powerful, you’re more likely to strike a power pose, but when you pretend to be powerful, you’re more likely to feel powerful.

Second question – we know our minds change our bodies. Do our bodies change our minds?

The mind of the powerful

Powerful minds tend to be more assertive, confident, optimistic. They feel they’ll win at games of change. They think abstractedly. They take more risks.

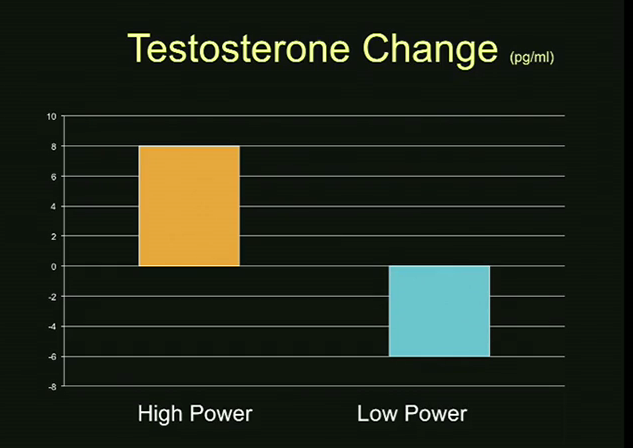

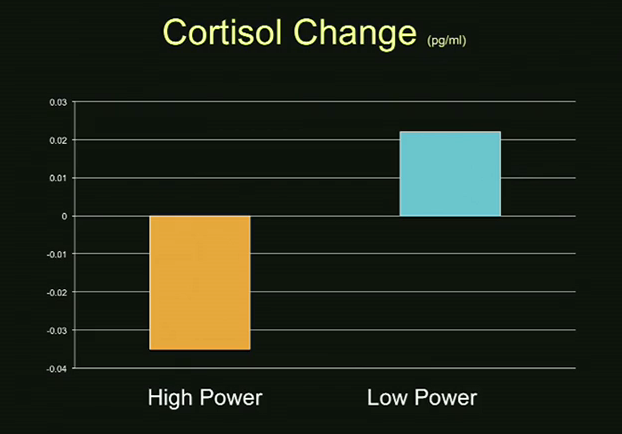

There are physiological differences too, on testosterone which is the dominance hormone and cortisol which is the stress hormone.

What we find is that high-power alpha males in primate hierarchies have high testosterone and low cortisol and powerful and effective leaders have the same.

What does that mean?

When you think about power, people used to always think about testosterone only because that’s to do with dominance, but power is also about how you react to stress.

So do you want the high power leader that’s high on testosterone but reacts terribly to stress or the one that’s high testosterone but not stress-reactive, the one that’s laid back?

We know that in primate hierarchies if an individual has to suddenly take over an alpha role, that individual’s testosterone goes up significantly and its cortisol levels drop significantly. So we have this evidence that the body can shape the mind, at least at the facial level, and also that role changes can shape the mind.

Power Pose Insight

Touching your neck is VERY low-power as you are really making yourself smaller and protecting yourself.

The two-minute test

We brought people into the lab, took a saliva sample and for two minutes we told them to take either low power or high power poses. We want them to start ‘feeling power,’ so we then ask them how powerful they feel on a series of items, and we give them a chance to gamble, and then we take another saliva sample.

Basically we give people two minutes to configure their brains to be assertive, confident and comfortable or really stress-reactive and feeling shut down.

It seems our nonverbals do govern how we think and feel, not just others. And our bodies change our minds.

Can power posing for a few minutes really change your life in meaningful ways?

You should use this in evaluative, social threat situations, like when you’re being evaluated by your peers e.g. public speaking, giving a pitch, doing a job interview.

We decided most people could relate to the job interview.

This is about you talking to yourself, not talking to other people, so it’s not about opening up MASSIVELY in your job interview. It’s about what you do prior to the job interview. What do most people do? They look at their notes, hunch up, making themselves small.

So in the bathroom beforehand, instead of that, try doing a power pose for two minutes.

We brought people into the lab, made them do either low power or high power poses for two minutes, then put them through very stressful job interviews for five minutes.

They are being judged during this time, and the judges have been trained to give no nonverbal feedback. They give no feedback at all – it’s worse than being heckled. This has been referred to as feeling like you’re ‘standing in social quicksand.’ It really spikes your cortisol.

We then have four coders look at the recordings of the interviews. They are blind to the hypothesis and they have no idea who’s been posing in which poses.

They say they want to hire the high-power posers. They also evaluated these people more positively overall.

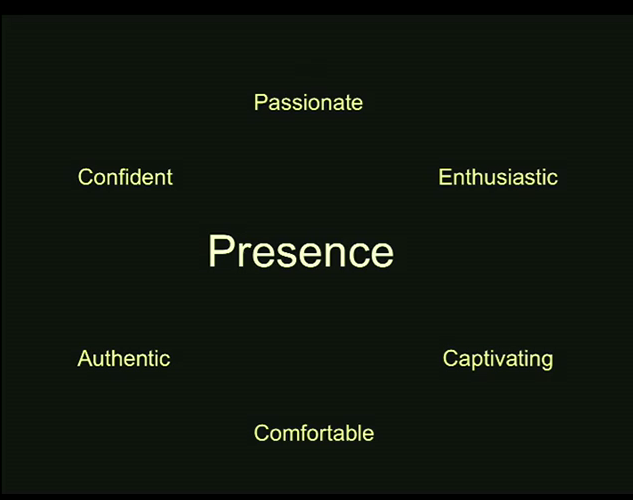

It’s not about the content of the speech, it’s about their presence and what they bring to the speech.

We tend to rate these types of people more highly on all these variables.

All these variables are to do with the SELF – their ideas are separate.This is what’s driving/mediating the effect

When I tell people our bodies can change our minds, our minds change our behaviour and our behaviour can change our outcomes, they say it feels fake. They said, “I don’t want to get there and STILL feel like an impostor, and that really resonated with me.”

“So I say, fake it until you make it.”

When I was 19 I was in a bad car accident, thrown out of a car, and I woke up in a head injury rehab ward and I had been withdrawn from college and I learned my IQ had dropped my two standard deviations.

I had identified with being smart and called gifted. I kept trying to go back to college. They told me I wouldn’t finish college and that there are other things for me to do, but that college wouldn’t work out.

I struggled with this – having my core identity taken from me. There’s nothing that makes you feel more powerless.

I worked and worked, and I worked and got lucky, and I graduated from college. It took me four years longer than my peers, and I convinced my angel advisor Susan Fisk to take me on, and I ended up at Princeton and I thought, ‘I’m not supposed to be here. I am an impostor.’

The night before my first year talk – and this is a talk to 20 people, a 20 min talk – I was so afraid of being found out that the next day that I called her and told her I was quitting.

She said:

“You are not quitting, because I took a gamble on you and you’re staying. You’re going to stay and this is what you’re going to do – you’re going to fake it, you’re going to do every talk that you’re ever asked to do, and you’re going to do it, even if you’re terrified, and having an out of body experience, until you have this experience when you say ‘oh my gosh I’m doing it. I have become this.’”

So that’s what I did.

Five years in graduate school, finally I’m at Harvard and I’m not really thinking about it, but for a long time I was thinking ‘I’m not supposed to be here.’

So the end of my first year at Harvard, a student who has not talked in class, who I warned that she had to participate or she was going to fail, she came into my office, and I really didn’t know her at all.

She was totally defeated and she said ‘I’m not supposed to be here.’

And that was the moment for me!

Two things happened – firstly, I realised, “oh my gosh I don’t feel like that anymore” but also she does and I understand that feeling!

Secondly, she is supposed to be here! She can fake it, she can become it, and I said, “yes you are, and tomorrow you’re going to fake it, you’re going to make yourself powerful, and you’re going to go into the classroom and you’re going to give the best comment ever.”

And she gave the best comment ever and people turned round and were like, “I didn’t even notice her.”

She came back to me months later, and she hadn’t faked it until she made it, she had faked it until she became it.

So she had changed!

I want to say to you, don’t fake it until you make it…

Fake it enough until you internalise it!

Final thoughts

Tiny tweaks can lead to big changes. Two minutes, two minutes, two minutes – next time just before you go into an intense evaluative situation, when you’re in the elevator or the bathroom, configure your brain to cope the best in that situation by getting your testosterone up and your cortisol down.

Don’t leave the situation with “oh I didn’t show them who I was.” Come out thinking, “yes I really showed them who I was.”

Try a power pose and share the science! People who need it most are those with no resources and no technology and no status and no power. Give it to them- they can do it in private.