Earlier this year, the European Court of Justice (‘ECJ’), the EU’s highest court, ruled that EU citizens have the right to ask search engines to remove links with certain information about them. Such requests may be made when the information is considered to be inaccurate, inadequate, irrelevant or excessive for the purpose of data processing. Google, Bing, Yahoo and other search engines must adhere to this law (which has become known as the “right to be forgotten”) by removing links to ensure the information does not appear on search results and remains undiscoverable to the majority of internet users.

This EU ruling is hugely significant, and it’s gaining increasing global attention, but what is the impact on the HR department in the UK and why are some hiring firms concerned about the decision?

While the debate rages about whether employers should or should not use the internet to investigate a candidate’s online presence before making a hiring decision, rightly or wrongly many firms are doing just this. In a recent survey, 77% said they now conduct internet searches of prospective employees, with over a third (35%) admitting they had found something which gave enough concern to reconsider the hire. On a positive note, however, a separate study found that almost 20% of respondents had discovered information online which sold them on a candidate, such as communication skills or a professional image.

Some recruiters are warning that the ECJ’s ruling could detrimentally impact the ability of employers to screen job applicants, resulting in an otherwise avoidable bad hire. This concern may be somewhat misplaced however. It is unlikely that a privacy-savvy job applicant would be capable of masking the results of a background check by simply removing links from Google’s search index.

Employers located in the EU, just like employers located anywhere in the world, may find that the scope of the ECJ’s ruling is limited. While the ruling requires that search engines purge their indexes linking to websites hosting the disputed content, this does not necessarily mean that the actual hosted content has been removed. In fact, the ECJ’s ruling only extends to search engines’ EU-facing pages. Conducting similar checks using Google.com or Google.ca for instance, is likely to present those missing links.

In the first three months following the ruling, Google received 70,000 take down requests, of which 53% were actioned on first application, with a further 15% removed following further review. These are big numbers and the search engines firms are taking things seriously by setting aside dedicated teams to manage what is a logistical pain-point. However, Google’s Advisory Council, which was created to navigate the ECJ ruling, met for the first time in Madrid on 9 September 2014 and again in Rome and Paris, has received criticisms from the EU regulatory community for attempting to set the terms of the debate.

Fortunately this ruling should not really cause any significant pain-points for recruiting organisations.

Clearly firms can continue processing online candidate investigations using search engines beyond the EU, but there are far more significant steps in checking a prospective employee’s history.

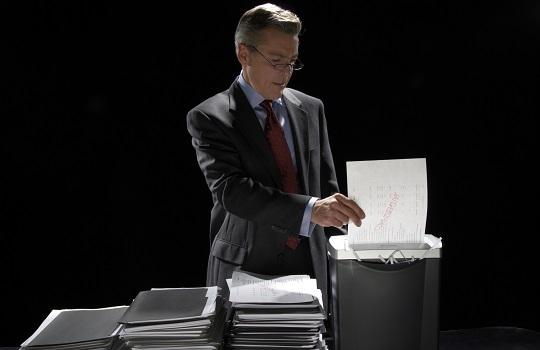

Whether background screening is conducted in-house or outsourced to a reliable background screening provider, organisations have long recognised that background checks involve more than a quick search of a candidate’s name on the internet. Criminal histories, credit checks, and employment and education verifications all form part of an employer’s arsenal to ensure they recruit the best people possible and minimize risks from within.

Google, and its competitors, can yield some information about candidates but companies should not put too much stock in what they can find.