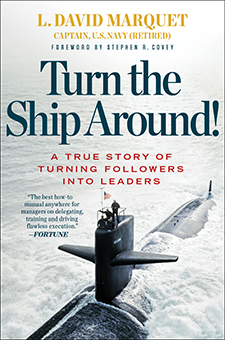

Title: Turn the Ship Around!: A True Story of Turning Followers into Leaders

Authors: David Marquet

ISBN: 978-1591846406

This book was reviewed by David Evans of Burn Bridge Associates.

The theme of this book is the change in leadership approach introduced by a Retired US Submarine Captain in order to get away from the blind obedience that results from a highly-directive leadership style, typical of the armed forces. His experience turned a poor-performing unit into a leading performer measured by a number of relevant indicators.

The key message of the book is that “Leadership should mean giving control rather than taking control, and creating leaders rather than forging followers”. This is the author’s essential tenet, and it is something he terms ‘the leader-leader model’.

After highlighting the poor scores in various metrics of employee engagement in the US economy (mirrored by similar levels of disengagement in the UK workforce), the author points to the practice of directive leadership in the US Navy, which divides the world into two groups – leaders and followers. He suggests the weakness in the leader-follower model is that people who are treated as followers tend to behave like followers, with expectations of limited decision-making authority and a diminished incentive to give of their best in terms of intellect, energy and passion.

Additionally in the leader-follower model, team / organisational performance is closely linked to the ability of the leader; which in turn leads to the development of a personality-driven leadership. Marquet’s antidote, the leader-leader model, has all organisation members becoming leaders, situationally. This results in people playing to their strengths, improving effectiveness, engendering commitment and strengthening the organisation’s capabilities and performance.

When he received his own command, he started reviewing the options for change and had a fundamental problem with the concept of ‘empowerment’: to have an empowerment programme, whereby he would empower his subordinates, seemed to be a reinforcement of the leader-follower relationship. Furthermore, he knew that he operated best personally when he was given specific goals and the latitude to select how best to accomplish them. Executing a series of tasks simply irritated him and caused him to ‘shut his brain down’. He concluded that competence could not rest solely with the leader but had to run throughout the organisation.

Leader-follower leadership also induces a mind-numbness, which results from subordinates not having to engage their brain: since tasks are handed out top-down, being responsible and accountable just doesn’t happen. And, it gets worse because when things get sticky followers tend to hunker down, reduce their field of vision and focus on not making mistakes – satisfying the minimum requirements and avoiding problems (even if, by confronting an issue they would be doing the right thing). Furthermore, people who are treated as followers treat others as followers when they come to lead.

The indicators of a directive, leader-follower leadership style can be easy to find. Low morale and a sense of disengagement can be discerned amongst a workforce. There is usually an absence of what is termed discretionary effort – people willing to go the extra mile. Additionally, the KPI set gives important clues: there will usually be a focus on error-counts and input measures (as opposed to an outcome-focus), which creates a morbid obsession with mistake-avoidance.

David Marquet determined to change the way things were being done on his ship by asserting the locus of control, divesting control and distributing it to the officers and crew. He sees control as making decisions concerning not only how we are going to work but also with what purpose. Doing this meant that some people (primarily department heads) would be expected to change their perception of their role: from a perceived position of privilege they would have to move to one with accountability, responsibility and increased workload. Interestingly, part of this change meant moving HR responsibilities into the line – holding the team leaders to account for resource-planning and scheduling, pay and rations, development and promotions, recruitment.

Marquet lists a number of actions that supported the shift of control to the teams and emphasises that divesting control needs to be supported by two important ‘platforms’: competence and clarity.

By competence, Marquet is referring to the need for people to be technically competent to make the decisions they make. When he refers to clarity he is raising the issue of organisational purpose: as decision-making authority is pushed further down an organisational hierarchy, it becomes increasingly important that everyone understands what the organisation is about.

Reviewer’s rating

This is an easy-read book about leadership in a very particular environment. In the traditional command-control context of the military it is refreshing to hear about someone trying something different. And it is good to hear about both the successful trials and the things that did not work so well. Marquet’s focus on providing detailed examples of what he did, why he did them and with what outcomes is instructive, even if a little repetitive .

This is a book that I think would benefit many line managers, for its food-for-thought messages; particularly those line managers in in traditional organisations with defined hierarchy.

Rating: 3 stars out of 5