Andrew's insight in this article is based on three years spent with the Royal Navy, examining their attitudes and. From this experience he wrote a book, Royal Navy Way of Leadership.

What is the single most important quality in a leader? For me, it’s cheerfulness. No one follows a pessimist. No one. Never.

I have spent the last three years writing the Royal Navy’s leadership manual, now issued to 15,000 naval staff. I’ve been struck, while training alongside the men and women of the Royal Navy, by the extent to which its engines of war run on “soft” leader ship skills. Cheerfulness is chief among them.

Although few environments are tougher than a ship or submarine, for officers leading small teams in constrained quarters, there’s no substitute for cheerfulness.

In fact, I’d go so far as to say that naval training rests on the notion that when two groups with equal resources attempt the same thing, the successful group will be the one whose leaders better understand how to use the softer skills to maintain effort and motivate.

I believe that the same principle holds true for business. Half of the Royal Navy works in an office, so the naval model matches business, government, charities and social enterprises.

So, to cheerfulness. Being cheerful is a choice. It has long been understood to influence happiness at work and therefore productivity. The cheerful leader broadcasts confidence and capability; and good organisations instinctively understand this. In the Royal Navy it is the captain, invariably, who sets the mood of a vessel; a gloomy captain means a gloomy ship.

And mood travels fast. Most ships’ crews are either smaller than, or divided into, units of fewer than 150 members— near the upper end of Dunbar’s Number, the magic HR number suggested by British anthropologist Robin Dunbar as the extent of a fully functioning social group.

Cheerfulness allows for urgency and velocity when things are going well, and for mistakes and forgiveness when they are not. Most organisations do not record how effective cheerfulness can be; but the Royal Navy assiduously records how cheerfulness counts in operations.

For example, in 2002 one of its ships ran aground, triggering the largest and most dangerous flooding incident in recent years. The Royal Navy’s investigating board of inquiry found that “morale remained high” throughout demanding hours of damage control and that “teams were cheerful and enthusiastic” focusing on their tasks; and “sailors commented that the presence, leadership, and good humor of senior officers gave reassurance and confidence that the ship would survive.”

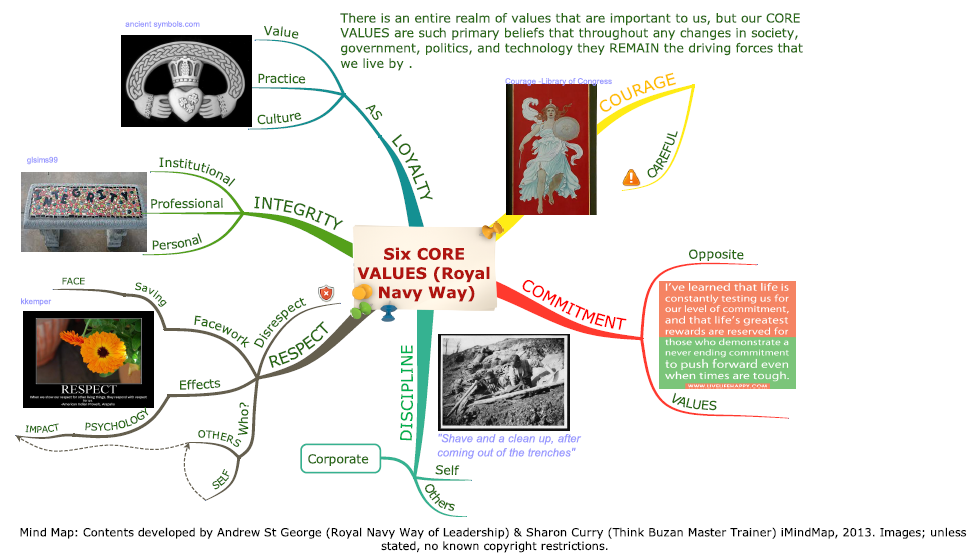

Turning up and being cheerful, in other words, had a practical benefit. And what does it cost? At the very most, you might have to set aside time to reaffirm your daily values, and a commitment to put cheerfulness among them. A values mind map might look like this:

How do you teach cheerfulness? Three things:

- Make every opportunity for your people to be cheerful. This sounds bland, but the Royal Navy takes every informal opportunity to demonstrate its usefulness and so should every organisation. To fill the dead time that invariably occurs during training exercises and other routine activities, for example, navy personnel are hugely innovative and inventive in constructing games, diversions and the like to encourage teamwork and cheerfulness,

- Focus on positives. Cheerfulness in turn encourages speed of thought, an outward-looking mind-set, and a willingness to talk. It even affects how people sit, stand, and gesticulate: you can see its absence when heads are buried in hands and eye contact is missing.

- Make the cheerful choice. In stressful situations Royal Marine commanders understand particularly well that cheerfulness is fueled by humor: one I met required his whole company to “sing for their supper” by telling a joke—any joke—in front of their fellow marines prior to eating.

Once you understand the collateral benefits of cheerfulness at work, it seems daft not to make it a priority. Such a skill is especially prized in the Royal Navy, an organisation that moves people quickly and often (typically, every two years) and requires them (perhaps s as a matter of life and death), to hit the ground running in their new posts.

As organisations become more fluid, and as managers expect staff to do more with less, and faster, cheerfulness is a little-understood yet vital attitude. As CEO of a public affairs firm, I tried to create a culture that trusted my people and expected them from the board down to the newest intern, to be able and willing to stand up and talk, in an impromptu fashion, about what they were doing. But I never really figured cheerfulness was a simple answer. I’d do things differently now.

The relevance of many of these techniques to the corporate workplace is obvious, not least in a world of rapid job rotation, team-based work, and short- term projects that are typically set up in response to sudden competitive challenges and require an equally fleet- footed response.

Conversely, empty optimism or false cheer can hurt morale. As one naval captain puts it, “Being able to make the uncertain certain is the secret to leadership. You have to understand, though, that if you are always über-optimistic, then the effect of your optimism, over time, is reduced.”

The Royal Navy and Royal Marines does challenging and difficult work by knowing its core values and making sure each individual can express them: cheerfulness, courage, commitment, discipline, respect, integrity, loyalty.

And which one of us would not want colleagues who believed in those things and acted on them?