"A man found a cocoon for a butterfly. One day a small opening appeared, he sat and watched the butterfly for several hours as it struggled to force its body through the little hole. Then it seemed to stop making any progress. It appeared stuck.

The man decided to help the butterfly and with a pair of scissors he cut open the cocoon. The butterfly then emerged easily. But something was strange. The butterfly had a swollen body and shrivelled wings. The man watched the butterfly expecting it to take on its correct proportions. But nothing changed.

The butterfly stayed the same. It was never able to fly. In his kindness and haste the man did not realise that the butterfly's struggle to get through the small opening of the cocoon is nature's way of forcing fluid from the body of the butterfly into its wings so that it would be ready for flight.

When we coach and teach others it is helpful to recognise when people need to do things for themselves. Sometimes the struggle makes all the difference."

This is one of our favourite stories we use when leading workshops. We use stories to pass on ideas and messages in a way which talks to the unconscious and well as the conscious mind. We know we have got it right when the story is repeated back to us by the next group of participants. Stories have many characteristics in common. They are also universal. Every culture uses stories to pass on knowledge and wisdom. It is not surprising therefore that neuroscience is beginning to find that our brain reacts to a story in a particular way, a way that is not seen when it just receives information from something like a PowerPoint presentation.

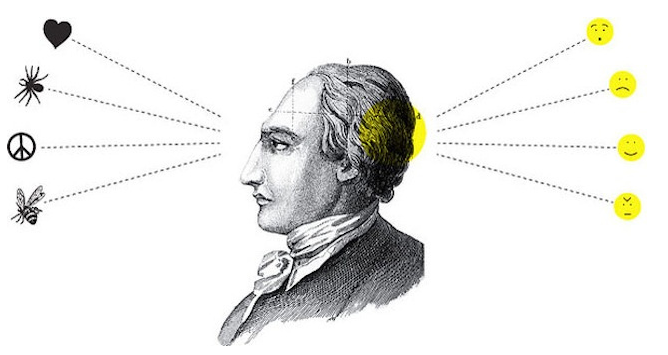

If we listen to a PowerPoint presentation with words and bullet points the language processing areas of the brain, Broca's area and Wernicke's area, are activated in order to decode the meaning. When we hear a story these areas are activated as well as all the areas that relate to the events in the story. For example if the story includes a description of the smell of a delicious pasta dish the sensory cortex is activated. If the story describes something unpleasant the disgust area is activated.

When we tell stories to others, specifically stories that shape thinking and pass on wisdom, the brains of the people hearing the story synchronise with the story tellers. Uri Hasson from Princeton found that similar brain regions like the insula and the frontal cortex were activated in listener and the story teller. The research suggests that storytelling creates a much deeper connection between people. The analysis also identified a subset of brain regions in which the responses in the listener’s brain preceded the responses in the speaker’s brain. These anticipatory responses suggest that the listeners are actively predicting the speaker’s upcoming words. This may compensate for problems with noisy or ambiguous input. Indeed, the more extensive the coupling between a speaker’s brain responses and a listener’s anticipatory brain responses, the research found, the better was the comprehension of the story.

Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, a neuroscientist and human development psychologist, found that when we hear inspirational stories, more blood flows to our brain stem – the part of our brain that makes our heart beat, regulates our breathing and keeps us alive. This makes you literally feel inspiration on the very substrate of your own biological survival.

It is possible that the reason stories are so powerful is that we think in narrative all the time. The area, known as the default system (named because we default to thinking about ourselves or others within a few seconds of brain 'inactivity') is activated when we think about ourselves and others. The default’s way of expressing thoughts is usually a narrative, at story, we are telling ourselves. So there is a consistency in how we ‘talk’ to ourselves and how we tell stories. A story, if broken down into the simplest form, is a connection of cause and effect. And that is how we think. We think in narratives whether it is about buying groceries, what is happening at work or thinking about our friends. We make up stories in our heads for every action and conversation. Jeremy Hsu found personal stories and gossip make up 65% of our conversations.

When we hear a story, we want to relate it to one of our existing experiences. That is why metaphors are used. While we are busy searching for a similar experience in our brains, we activate a part called the insula, which helps us relate to that same experience of pain, joy, or disgust.

The graphic describes this:

Matt Lieberman has been studying what happens in the brain when people hear an idea that they will pass on to others and relay the idea in such a way so that the second person will also pass the idea on. Lieberman and his colleagues designed an experiment to explore what is going on in the brain when we first encounter an idea that is destined to spread successfully. You can download a video of Lieberman describing this work at the NeuroLeadership Summit .

What they wanted to see is what happens in the brain of the person who heard an idea that they will not only share with someone but that person will also share it. In HR terms, what happens in your brain when your strategic idea or solution to a problem convinces others to tell their teams or network? The expectation was that they would find areas of the brain activated that are associated with memory and deep encoding. That is areas that are used to hold onto critical information. In fact, those parts of the brain did not stand out in the study. They found strong activity in the brain’s default system, mentioned above – a network of brain regions central to thinking about other people’s goals, feelings, and interests.

Before this research it was assumed that when people are exposed to new information, a new story, they are assessing whether the information is sufficiently useful to them to pay close attention and try to remember. The experiments found we utilise our social concerns when we take in new information. People are testing whether the information is of value to others who are important to them, and not just whether it is of direct personal value.

Lieberman calls this being an information DJ – people don’t just think about whether the information is useful to them but who else it will be useful to. They have others’ interests in mind when initially hearing the information and the more they feel it is important, the more they are able to pass the information on in a way that also resonates with others. Lieberman says this probably activates the rewards systems in the brain, increasing the person’s sense of reputation in the group. The better leaders are at understanding what will appeal to others, the more likely they are to pass on the right information which will appeal and spread.

In other research that supports Lieberman’s findings, Raymond Mar, a psychologist at York University in Canada, analysed 86 fMRI studies and showed there is substantial overlap in the brain networks used to understand stories and the networks used to understand others especially when we are trying to understand the thoughts and feelings of others.

Since the regions activated are associated with the ability to simulate the minds of others, it appears that to be an effective influencer you need to spontaneously think about how to communicate information to others in a useful and interesting way when you first hear the information yourself. This is called the encoding stage.

The findings also add to an emerging literature on the link between the default system and social communication more generally. For instance, Greg Stephens and colleagues recorded the brain activity from speakers and listeners during natural verbal communication and found that when the listener’s brain activity in the default network mirrored the speaker’s brain activity, there was greater communication and understanding between both of them. The regions activated were the same key regions found in the Lieberman research including the medial prefrontal cortex and the precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex.

As Lieberman and co say, the findings have a number of important implications for the spread of ideas, norms, values, and culture. It suggests that this depends more on the influencer’s social-cognitive abilities, use of emotions, and motivation, and less on IQ-type intelligence. None of the stages involved recruited brain regions associated with higher-level abstract reasoning and executive functioning.

So the next time you want to influence ensure you are putting yourself in the shoes of who you want to convince and to be especially successful or are struggling with getting people on board with your projects and ideas, tell them a story that has an ending which is what you had in mind. Stories are a powerful way to plant ideas into other people's minds.

8 responses

Also, do you know any more

Also, do you know any more interesting articles I can read about storytelling that involves neuroscience/psychology?

Sensational!

Jan, this is a remarkable article, so first of all thanks for writing it! I loved the story at the start and I will certainly pass it on to my friends 😉

I love studying about story writing, and articles like these are refreshing to read because they use scientific data to back up the theories. It's so interesting to see that when people hear an idea, they assess it based on how others will value it. That's probably why I always want to tell my friends about a game or movie after I've played it.

I'm a storyteller myself, and I wrote this article about how to write a story. In there, I state that emotion comes from meaning, and I think this article definitely supports that theory. When something is meaningful, it might also be what you think others find meaningful. I'll certainly keep in mind this concept of Information DJ when I write my future stories.

Cheers!

Great story!

I will pinch that one!

People love stories

People have always loved stories. It can be said that stories are what make us human in the first place – the concept of narrative.

Teaching stories can be immensely powerful, because people remember them in a way they remember very little else. We remember the narrative sequence, the payoff, and sometimes we remember the meaning. They can illustrate difficult concepts in an easy-to-recall manner, and often the bombshell of meaning is hidden behind the humour.

My current favourite:

A man goes to a golf pro and asks for a lesson, never having played before in his life. The pro takes him out to a par 4 hole, puts the golfball on the tee and hands him a club.

"Now what?" asks the man.

The pro points at the flag on the greenway. "Hit the ball as close to that flag as you can manage." he says.

The man duly swipes, and the ball arcs off down the course. They walk along, and when they get to the green, the ball is around 6 inches from the hole.

"Now what?" asks the man again.

"Knock the ball into the hole." says the pro.

The man rounds on the pro angrily. "Why the heck didn't you say that in the first place?"

Excellent article – thanks.

Thank you

for you comments. I am pleased that you find the article interesting. I agree using stories in workshops is very powerful and can also be a great tool for leaders/managers.

Really great article. Enjoyed reading this.

Really great article. Enjoyed reading this. Good learning.

During Training session, we are telling story, it is refreshing the mood of participants and make learning simple. Further Leaders/Managers, specially, can use the power of a good story to influence and motivate their teams to a new heights.

Regards,

Both/and works

Thank you for your comments. Yes both/ and works for leaders in the types of cultures/industry you describe. In our own work we find being able to give the science behind the 'soft' skills reduces resistance and helps leader to be more open to change. Good luck with the work I am always interested in hearing examples of how applying the science worked..

The power of story

Thank you so much for this article sharing the relationship between story telling and neuroscience. I coach a number of executives who are in science based cultures or who are scientists themselves. When we talk about story telling as a way to influence and persuade, some of them are resistant because they prefer to rely on data. They find it difficult to make the shift to "both/and" data and story. This article will appeal to their data and science based way of processing and accepting the value of stories to create connection, enthusiasm, and engagement.