As human beings, we are culturally programmed to view the world from our own national perspective. This makes us blind to our own culture. Just as fish don’t see water, leadership teams from the same nation as the company, or who have worked at the company for a long period, may struggle to see when a potentially derailing cultural dynamic is at play. National cultural traits only change slowly, over decades or centuries, and are often invisible to the organization. They are implicitly embedded in the culture. Companies and people don’t talk about them, they are just there as implicit assumptions, and thus difficult to see – for fish and for us!

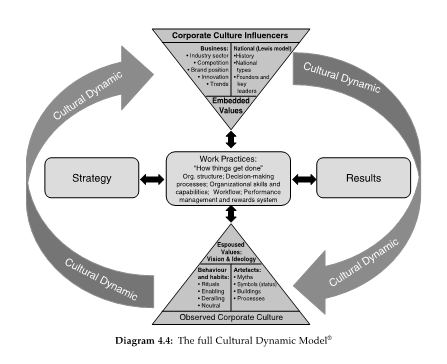

A change of strategy can start a domino effect of changes in the work practices, which over time dynamically impacts the corporate culture. A cultural dynamic describes a sequence of systemically reinforced effects where the work practices, corporate culture and strategic intent dynamically interact to either reinforce a culture or change it! A cultural dynamic describes the unintended consequence of a strategy change, often rooted in national traits that change a corporate culture.

Let’s share an example of what we mean by a cultural dynamic.

The American culture is at its best when displaying vibrant individualism, entrepreneurial spirit, risk-taking, innovation, ambition and results orientation combined with a focus on making money. “The business of America is business”, as they say. These traits very much characterized General Motors in the first part of the 20th century, when it emerged as the dominant American car company. Initially, GM lost out to Ford’s one-product, one-color (black) and low-cost car strategy, as it focused on a strategy offering multiple car brands, from the entry-level Chevy to the up-market Cadillac, and in multiple colors. However, by the 1950s, GM had become the leading industrial company in the world with over 50% market share in the US car market.

A very strong cultural dynamic emerged, fuelled by GM’s success and strong American values. It was based on Alfred Sloan’s belief in decentralization where each individual brand would cater to a specific customer segments and be run as an independent businesses. Sloan was also a strong believer in rational (un-emotional) decision-making, and would allow for different leadership types to thrive, as long as they created shareholder value and were on the ball leading their business from the front.

However, to avoid a break-up, at a time when Sloan’s influence had started to wane, GM felt forced by the US government to stop focusing on gaining share, and instead focused on increasing profits by reducing cost. It chose a CFO as the new leader, rather than the usual ‘car man”. Over time GM developed a more introverted, bureaucratic and customer-distant culture with increasingly uncompetitive products as the shared platforms and components over time made the individual car brands, Cadillac, Buick, Pontiac, Oldsmobile and Chevrolet etc, less distinctive.

A new cultural dynamic emerged, where the internally promoted executives, increasingly under threat from the outside world, would shelter themselves from it in a clubby white male culture on the top executive floors of the GM building – focused on finances, numbers and analytics. In this case, GM also exemplifies a potentially derailing side of the American corporate culture, which can be hierarchical, bureaucratic and command-and-control oriented, if not managed in the mature phase of a company’s lifecycle or in a crisis. The term “red tape” was, after all, invented in the USA.

When GM changed its focus from market share to profitability, the board and management did not intend the organization to adopt an insular and increasingly bureaucratic and clubby culture that over time distanced itself from the customer and the organization. It simply happened by itself, as changes in the organizational focus and management practices started to impact the corporate behaviors and decision-making processes and, in turn, reinforced subtle changes in the corporate structure, that over time would reinforce this new culture.

Aspects of deeply-rooted American values also played a role in this. This cultural dynamic was reinforced by American short-termism, where the short-term cost cutting for instance would see profitability increase the next year – or a new initiative like Saturn car which was launched with much fanfare and enthusiasm (and huge investment), where similarly any positive news would be interpreted as a proof of the strategy working. Thus, a pattern emerged where repeated bursts of American short-term optimism, fuelled by the drive for leaders to take action, would let management believe that the newest strategy was working, often helped by a positive turn in the cyclical demand pattern – only to be disproved by the market a few questers later – as the market share erosion would continue. Ultimately, after many years of steadily decreasing market share and huge losses, the US government in 2009 bailed out GM – despite having been managed by highly competent leaders and world supervised (in the last 25 years) by a world class board.

As leaders, it’s important for you to observe that a company under crisis often will revert to its core national culture, as the psychologist in post-traumatic experiences would predict. However global it may be, an American corporation under pressure will often become more American. It will become more hierarchical, more command–control oriented, more dogmatic and more rigid, showing another side of the American corporate psyche. The finance department will increase its strengths, and the employees will become more individualistically focused on myopic objectives and less team oriented. The structure may change to one where the global BU structure will be managed out of the USA, with less power to the regions. It is indeed rare that a crisis will make a company more global and inclusive in its perspective. The same obviously goes for German, Indian, French, Brazilian, Chinese, Japanese, Danish, Italian, Finnish and Korean companies. They will all react differently to a crisis, as they revert to their own national uniqueness.

So what should the board and management learn from this?

1. It is the ultimate responsibility of the board to promote and ensure the diversity (of thinking), even if the day-to-day execution may not require such diversity, to avoid the fish can’t see water syndrome.

2. The board and management should establish a regular methodology to both identify cultural dynamics that can help accelerate performance, and potentially derailing cultural dynamics that may hold back performance – before it happens. They may need outsiders to help them do so.

3. No company and no leader from any country can afford to ignore the effect of the national cultural heritage during a period of crisis! Boards and management must watch out for myopic thinking and nationally rooted justifications, which may reduce operational agility and the ability to think clearly – to the detriment of shareholders!