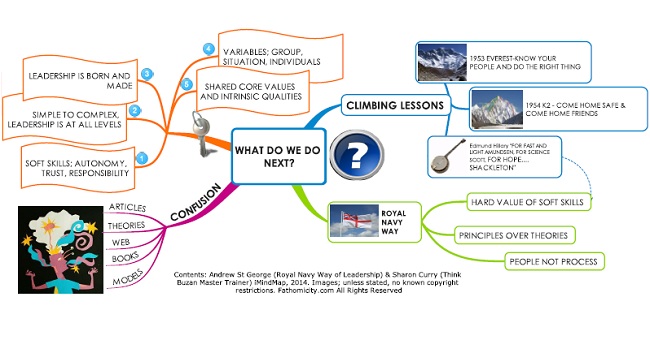

Andrew’s insight in this article is based on three years spent with the Royal Navy, examining their attitudes and. From this experience he wrote a book, Royal Navy Way of Leadership.

Every time we put ourselves in dangerous situations there are leadership lessons to be learned. Mountaineering and military operations are some of the best places to find a combination of experience and reflection.

In 1998 I met two men who had vital intelligence from their own front line. I was not expecting to meet either. The first was Achille Compagnoni, first up K2. We met by chance and chatted in his small hotel in Cervinia, under the Matterhorn. He’d fallen out with Walter Bonatti, the greatest Italian climber of his generation, over events on K2 that July 1954 – they never resolved their differences.

Things had gone wrong, somewhere on the high ice-fields, and even two generations later, were never put right. The leadership lesson in mountaineering is always “come home safe, and come home friends.” That had not worked for Compagnoni and Bonatti.

The other man was Ed Hillary, first up Everest in 1953. I met him at the Hay-on-Wye Festival where we were both speaking. Thinking of Compagnoni, I asked him what a good expedition leader does when things go wrong.

He answered obliquely: if you wanted fast and light, you needed an explorer like Amundsen; for heavy scientific discovery, Scott; but if you were in real trouble in a difficult place you’d need Captain Ernest Shackleton.

Why Shackleton?

Because he understood his people and was prepared to do the right thing. That’s a good motto for any leader – know your people and do the right thing.

Shackleton certainly did that. In October 1915 with his ship in the grip of the ice floe, facing an epic journey over land and sea, he and his crew emptied their pockets and tipped all non-essentials – watches, coins, glass photographic plates – into the freezing waters.

Shackleton took the wardroom banjo with him – moral medicine, he called it. He knew what his men didn’t.

He knew that the uplifting effects of music were key to survival in the dismal Antarctic wastes. That is what great leaders do.

Shackleton was lucky enough to have had Royal Naval training, a kind of training that knows the hard value of soft skills, that recognizes people rather than processes, and that knows principles rather than theories.

When his expedition went wrong, he knew what to do. All leadership comes down to the question: what do we do next?

How well do we really understand leadership?

It’s much taught, much studied, and little understood. A quick look at the academic literature shows that while hundreds of leadership articles were written between 1950 and 1990, many tens of thousands have been written in the last twenty-five years.

The academic inflation has its counterpart in the commercial world, where daft management and leadership theories abound and where soul-destroying nonsense is pedalled by privateer consultants selling “scope shifting” and “transformational experientials.” I see what they mean, but the jargon is mind-numbing.

Despite this, I’m optimistic about the state of leadership because I have spent time with people just like Shackleton and because over the last three years I have been writing The Royal Navy Way of Leadership, the handbook for 15,000 Officers and Senior Ratings.

Writing the book taught me that in the Navy (and in the wider military) we have a world-class management and leadership style on our own doorstep and tested over hundreds of years.

The Navy understands profoundly the practical uses of commitment, loyalty, integrity, respect and cheerfulness in ways that mostly evade the commercial and public sector.

And it’s all about getting things done in small groups (half the Navy works in an office, just like you and me), which is where we spend most of our working lives.

The Navy environment

Nowhere have I found a more cheerful, consistent and yet flexible working environment. I followed officer training with the Surface Fleet and with the Royal Marines: I spent long periods on or under the sea. I hung from helicopters and studied in classrooms. I got wet, cold, dirty and exhausted alongside others, and I got smarter about leadership. The same would certainly be true for experience learned in the wider military.

The military has so much to teach British businesses, public sector, charities and government. The military excels at getting things done by treating its people properly. It runs on high emotional intelligence alongside the command and control that sets the framework for operations. This was a revelation to me. After twenty years in universities and in business, I found in the Navy lessons I had never seen elsewhere.

So that you don’t have to get muddy, wet, cold or tired, here are my five takeaways:

- Leadership comes down to soft skills. People thrive on autonomy, trust and responsibility – the fruits of a soft skills ethos. Differences of 25% in employees’ performance can depend upon a sense of wellbeing at work – according to a French survey. Studies at Warwick Business School show that happier workers are over 10% more productive and unhappy workers 10% less. Feelings count.

- Leadership exists at all levels, from simple managerial tasks to complex strategic and political planning: the qualities are the same but expressed differently according to the context.

- Leaders are both born and made: that is, leadership is a combination of inclination and experience, and the product of teaching and learning. Leadership is not a dark art; it can be learned through personal experience and the experience of others, from thinking about the principles involved, and from asking questions and listening to others.

- Leadership within any group tends to alter to match a number of variables: what the group is doing and where, and its specific situation and that of the individuals who are part of it. Leadership style derives from all messages, verbal and non-verbal: how people gesture, sit, stand, dress, speak, listen and so forth.

- Leadership comes not only from a set of qualities intrinsic to any leader, but also from the core values shared with all those in his or her team: Taken together, these form a way of seeing and doing – a set of behaviours – based on shared practical means, intellectual approach, moral principles and emotional expression. So core values are vital to good leadership because they provide the context in which leaders and followers behave.

These five lessons help to answer the question: what do we do next? As for me, I am fortunate to be working alongside Sharon Curry (ex-Royal Navy) whose input and brilliant mind maps provide a visual means of communicating the book’s message while also creating connections to the bigger leadership picture in the commercial world.

Further articles from Andrew St George:

- Cheerfulness is the most important leadership quality

- Do you need an HR department?

- Ethical leadership – do things right, do the right thing

If you’d like to email Andrew or Sharon, who works with Andrew and produced the mind map above, you can do so on astg@fathomicity.com and sgc@fathomicity.com respectively