In this series, originally posted on our sister site TrainingZone, we look at a number of myths which have grown up around good learning strategy and design and take the findings from neuroscience to confirm or bust them. This series is drawn from the book Brain-savvy Business: 8 principles from neuroscience and how to apply them. Jan is giving away 20 books, one to each reader who contributes a short example of how they will use the ideas in the series or of how they have applied neuroscience to learning.

One way to capitalise on the science of how the brain learns is to use a variety of different ways to help learners make the most of the learning experience.

For example, we know that the brain retains information best when it arrives in small chunks, over a period of time and with opportunities for reflection and practice in between.

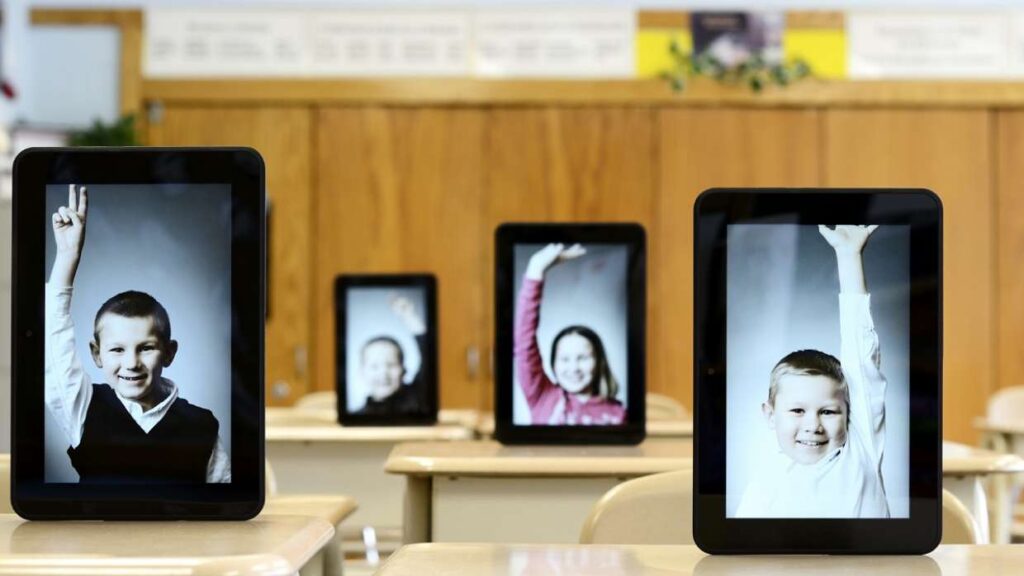

We also know that the brain likes to learn with others. That makes virtual learning programmes and webinars and related technology perfectly suited to effective learning. Webinars can mean that learners get maximum benefit from the time they put in.

We know that the brain likes to learn with others.

Be clear about expectations

There are several considerations which make remote or virtual programmes work.

When designing such a programme outline what’s expected of participants and instil the right mind-set for getting the most out of the learning.

You could, for example, prepare participants to be responsible for their learning by asking them to select a sponsor from within their own organisation and including a Personal Learning Agreement, a contract between the learner and their manager or sponsor that helps them keep track of their progress and defines the support they require to apply the learning.

Attention spans

Various studies have demonstrated that our brains can only give something our full attention for less than about 20 minutes.

After that time, it’s less and less likely that we’ll retain information we’re presented with.

What happens when we lose and regain our attention?

What happens in the brain when we lose and then regain attention is governed by the two separate systems.

Dorsal attention network

There’s the dorsal attention network, located high in the brain, which is active when we chose to focus on things like goals or intentions.

So listening to the boss explain their vision for the new leadership behaviours and working out what it means for us is likely to be activating this system.

Ventral attention network

The second system is the ventral attention network. This directs attention to things coming in from our senses and is effectively a safety system, keeping us alert to potential danger.

The problem comes when the alerts are not central to our continued survival but relate to less critical matters – like a new email landing in the inbox and your phone going ping.

The two systems work together – the dorsal system gets a bit of a rest when the ventral system directs our attention elsewhere. This rest also gives the dorsal system a chance to refocus and notice what might have changed while it had been distracted.

Of course, all of this can happen in less than a second, sometimes without us even being aware we’ve switched focus.

What about the brain's braking system?

It’s likely that in a learning environment there is also another system which is active – the brain’s braking system. [PDF]

This inhibits our impulses, and whilst it’s useful in stopping us from flitting from one thing to the next, it tires us out. That’s another reason why taking frequent ‘brain breaks’ is important.

These features of attention have an impact on how our memory works. As we might expect, constantly flitting from one focus to another (as when we’re multitasking) has been shown to reduce our ability to retrieve information later on.

You should aim to divide learning into small, easily assimilated chunks to accommodate the brain’s 20-minute attention span

In virtual programmes it’s therefore even more important to set some ground rules about attention and dissuade people from multitasking, such as doing their email whilst listening to the webinar.

One way of helping people focus is to require frequent input from participants and to keep the pace lively and interactive. Varying the content and even the webinar leader also helps.

Structuring virtual programmes

In our experience programmes which are virtual or which contain a mix of face-to-face or webinar type learning need to be designed specifically. Just putting a face-to-face programme online doesn’t work very well.

One way to structure a virtual or webinar-based learning event is to include three elements to each phase:

- knowledge

- processing

- application.

Knowledge is either introduced in the workplace or the information is presented in a relevant context, perhaps in the form of a video, some reading, an interview with a client or colleague, a self-assessment test or a reflective process prompted by questions as mentioned above.

The processing stage begins when the group comes together to discuss the information, to think about the reasoning behind it and its potential application.

The third element – application, takes place in the workplace and is where the learning is applied and put into practice. (Take a look at the third article in this series for more information).

Delivering content

You should aim to divide learning into small, easily assimilated chunks to accommodate the brain’s 20-minute attention span:

- Include multi-media messaging that engages multiple senses and increases neurological connections.

- Maximise brain-based rewards by ensuring positive CORE (see our video for more on CORE) and personal rewards for learners

- See if you can get the participants to connect with one another and agree the ways of interacting through clear, simple ground rules.

- Vary the activities so the brain has a chance to refocus and reset. Ideally these new activities use different parts of the brain’s processing ability.

For example, if people have been sitting listening for a while then they’ll welcome a chance to do an activity like use a webinar white board or ask questions or reflect and write.

It’s easier to create a new behaviour than to change an old one.

You might also include on the learning platform an online library of tools, frameworks, videos and techniques tailored to the learners, enabling them to form a social learning community in which they can share their learning, successes and tips for applying the learning, thus tapping into the brain’s need for social connection.

Changing behaviour

The application of new learning involves convincing people to change their work habits.

Neuroscientist Kevin Ochsner estimates that humans act according to habit 70%-90% of the time, and are guided by deliberate mindful actions only 10%-30% of the time.

It’s also worth knowing that it’s easier to create a new behaviour than to change an old one.

So when designing a programme, make sure you include ways for participants to work out precisely which behaviours and habits will help them succeed. They are more likely to be successful when they:

- Make the goal public. We like to be seen to keep our commitments.

- Work with someone else on the new habit, like getting feedback from a buddy or asking a colleague for support.

- Plan for what might derail them. Anticipating stumbling blocks makes them easier to overcome.

- Build in rewards for each step towards success.

Technology

There is, even now, limited use being made of technology such as webinars and social learning platforms as an integral part of the learning methodology.

This is especially true for programmes involving more senior people. What’s more, the small number of virtual programmes that are being provided are typically under-supported. Webinars are more often used as short, one-off sessions rather than as a methodology to support on-going learning or to deliver programmes across geographies.

They are usually stand-alone initiatives with little follow-up or embedding.

However, when this technology is properly exploited, the benefits to learning are unarguable, as are the cost savings in travel and down time.

Jan is giving away 20 books, one to each reader who contributes a short example of how they will use the ideas in the series or of how they have applied neuroscience to learning.