This article was co-authored by Gail Wise, Partner at enVision Performance Solutions and Clinton Wingrove, EVP and Principal Consultant at Pilat HR Solutions.

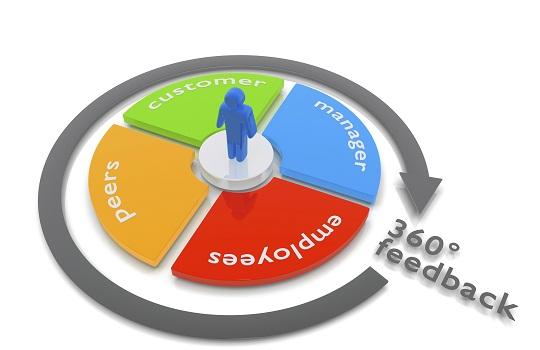

Multi-rater feedback, or ‘360’, has been in widespread use since at least the late 80s, with almost all large corporations using it in some form or other. Organisations employ it for a wide array of reasons including leadership development, succession management, improving understanding of what it takes to be successful in the organisation and managing performance.

How Does 360 Lead to Behaviour Change?

At its core, 360 rests upon the assumption that improved self-awareness will lead to improvements in behaviour. This is not a new assumption; Paul Brouwer, in the 1964 Harvard Business Review classic “The Power to See Ourselves” explored the importance of helping leaders grow by seeing the differences between their own self-image and the way others see them. Brouwer puts it bluntly: “As a matter of cold, hard, psychological fact, a change in behaviour on the job…means a change in self-concept.”

360 would seem to be uniquely positioned to help leaders improve self-awareness and change their self-concept. Because 360 provides inputs from multiple sources, it gives leaders the opportunity to look in multiple mirrors – to understand the perceptions of bosses, peers, direct reports and others. This more well-rounded view of performance helps leaders see themselves as others see them. The beauty and the challenge of 360 is that this more well-rounded view is both realistic and often not particularly straightforward. Differences in perspectives, varying interpretations of rating scales, different opportunities to observe the leader as well as actual differences in behaviour can each affect how others see a leader and can make interpretation challenging.

What Behaviours Need to Change?

A more fundamental challenge in 360, however, is determining what to measure. As mentioned, the ultimate goal of 360 is a change in self-awareness leading to a change in behaviour. Consequently, organisations need to think carefully about what types of behaviours they target in their 360 instruments in order to ensure that the self-awareness fostered is as productive as possible. What is measured sends a message about what is valued.

Most 360s currently on the market focus on ‘competencies,’ which have been defined by Klemp (1980) as “underlying characteristics of a person which result in effective and/or superior performance on the job.” Consequently, the self-awareness that the leader derives from using the 360 focuses primarily on positive aspects of leader behaviour. So the messages sent to feedback recipients are essentially two-fold: “you exhibit this positive behaviour well” or “you could exhibit this positive behaviour a little more or a little less.” For example, a leader might learn through 360 that s/he is seen as excellent in planning and organising (a positive behaviour), but could exhibit a little more coaching (another positive behaviour) and a little less follow-up (yet another positive behaviour).

The issue, though, is that in spite of the recent movement to accentuate strengths, positive aspects of behaviour are not necessarily the ones that underlie leader ineffectiveness. Hogan, Hogan and Kaiser, in their 2011 review of research on why leaders fail, phrase it succinctly: “Failure may be less about lacking ‘the right stuff’ and more about having ‘the wrong stuff’ – dysfunctional characteristics associated with failure.” Arrogance, interpersonal quirks, Machiavellian politics or outright deviousness aren’t measured in the ‘typical’ 360 instrument and are thus exposed peripherally, if at all. Hogan et al.’s review emphasises the problem for a 360 assessment instrument that fails to examine such ‘wrong stuff’ behaviours: “Every study of managerial failure…points to ‘overriding personality defects’… as a key issue.”

Interestingly, though, in addition to focusing only on competencies, many 360 instruments look at the frequency of behaviours. While that works with positive behaviours where ‘more’ is often ‘better,’ that is not the case with negative behaviours rooted in character flaws or interpersonal issues. Such ‘wrong stuff’ behaviours are likely to be exhibited less frequently and often under periods of stress. They don’t have to occur often, however, to be searing in their impact. Leaders who behave unethically, who lie or who are patronising or bigoted do not need to exhibit such behaviours routinely in order to irreparably damage their effectiveness.

Implications for 360 Instrumentation

The implications for developing or selecting a quality 360 feedback instrument are clear. Because what is measured by the 360 instrument shapes the messages that leaders will receive from it, the 360 instrument should assess both positive (‘bright side’) and derailing (‘dark side’) behaviours. If an organisation’s 360 instrumentation does not provide a structured opportunity for raters to provide feedback on the full range of leader behaviour, it will not help leaders address ‘dark side’ issues that are torpedoing their effectiveness.

So what might this look like? Certainly a 360 instrument should include a section that looks at ‘the right stuff,’ with questions that examine ‘bright side’ behaviours. ‘Right stuff’ questions typically look like the following, where more of the behaviour is typically better:

- Treats others with dignity and respect.

- Delivers what s/he promises.

A lower score on ‘right stuff’ questions typically is interpreted as ‘the leader is not doing enough of the behaviour.’ So, then, a lower score on ‘treats others with dignity and respect,’ for instance, would signal the 360 participant that s/he needs to behave more respectfully towards others; and one hopes that either other items or the comments shed light on what ‘more respectfully’ should look like.

In contrast, ‘wrong stuff’ questions ask directly about ‘dark side behaviours.’ ‘Wrong stuff’ questions might look like these:

- Doesn’t admit when s/he has made a mistake.

- Says one thing and does another.

These examples show both the clarity and the potential power of the feedback that can be provided by character-based or interpersonally-focused ‘wrong stuff’ items. Not only does this type of item measure ‘wrong stuff’ behaviours that are unlikely to surface in a structured way in a ‘competency-only’ instrument; it can do so in a way that hits home – hard. Receiving a less than desirable rating on ‘says one thing and does another,’ for instance, packs a punch that is difficult to ignore.

In his 2009 book Derailed: Five Lessons Learned from Catastrophic Failures of Leadership, Tim Irwin said that “derailment is not inevitable but, without development, it is probable.” A 360 intervention that fails to identify significant performance issues by not tapping ‘wrong stuff’ behaviours is not just a lost opportunity. It may actually contribute to derailment by lulling an ineffective leader into a false sense of security (“see, nobody thinks I am all that bad”).

Conclusion

The promise of 360 feedback is a profound one – that by helping leaders improve their self-awareness, they can grow, develop and shape their behaviours to become even more effective in their chosen realm. Back in 1964, Brouwer phrased it even more inspirationally: “Strong leaders fulfil themselves as they live lives that are an unfolding of their potential…The self-concept of the strong executive is a constantly evolving, changing thing as they continuously realise themselves.”

Careful selection of 360 instrumentation to ensure a balanced look at both the ‘bright side’ and the ‘dark side’ of leader behaviour is one way to realise even more self-reflection, personal evolution and business impact.

3 responses

Assessing unhelpful behaviours

What an excellent article!

With regard to the 'dark side' behaviours, I agree that 360 degree appraisal may be far less likely to pick these up – not just for the reasons stated, but because not all appraisers may be inclined to comment negatively, or even objectively.

Far better, quicker and simpler in my experience, and often more reliable, would be the Hogan Development Survey (HDS) – a psychometric instrument specifically designed to pick up potential 'dark side career derailers'.

This is a much less expensive on-line tool, whether for personal development, coaching or even recruitment, than 360 appraisal. Although it is self-scored by the participants, it actually measures what others think of us rather than what we may think of ourselves. (Also allied to this are the Hogan companion HPI questionnaire, to measure the 'sunny side' high performance potential, and the MVPI questionnaire that measures values and organisational fit. There is also a related 'Safety Report' to assess employees' attitudes to risk and safe working, especially helpful to assess those working in high-risk environments.)

If anyone wants to know more, I use Three Minute Mile in the UK to train users and help administer these Hogan reports – http://www.3minutemile.co.uk (0) 845 130 5927 – lwhom I find to be really helpful and knowledgeable.

Jeremy Thorn

Should 360 be used with non-leaders?

Paddy refers to the long-standing issue of whether 360 should be used with non-leaders as it can be "cost-prohibitive."

I have been working with 360 since 1984 and this issue has always interested me.

I go further and say that many (most?) 360 processes are ineffective and add more cost than return. However, I passionately believe that implemented well, as Gail articulates, this can be one of the most effective levers for individual growth. Like most tools, there are two critically important questions. Do we have the best possible tool? Do we know how to use, and will we use, that tool to very best effect?

In some organizations, 360 is used extremely well. Individuals are either selected or given the chance to self nominate (rather than trivialising the process by "sheep dipping" everyone); a best-fit tool is used to enable the participants to identify true development priorities (not merely perceived strengths and weaknesses); the feedback is facilitated so that participants engage, understand, prioritise, focus, and action plan (rather than "staring glazed-eyed into the mirror"); and management attention is paid to the development actions and outcomes (rather than simply being "interested" in the numbers and benchmarks).

Designed and implemented well, 360 can trigger, enable and reinforce significant personal development with direct impact on the bottom line … for virtually anyone.

Clinton

Thoughts about accentuating strengths and ‘dark side’ behaviours

Hi Jamie,

Great article, and I’ll be adding Tim Irwin to my reading list 🙂

I agree that the strengths of an employee* or leader are valuable to understand, but they do not often present the biggest opportunities for the individual to learn from the exercise and focus their development.

I suspect that the movement to accentuate strengths stems from a common problem with 360s: the results are often confusing and lead to a debate on the scores given for areas that are shown as weaknesses. This defeats the exercise by using up the time that should have been used to develop an action plan for improvement, and by leaving the leader feeling demoralized and unclear on their top priorities.

You’ll recall my strong views on this from our chat at CIPD – and that I feel that this is a problem with the tools used and not the 360 process itself. Hence why we’ve created Spidergap and are seeing it get radically better results (- subtle plug!)

With regards to the behaviours, I’m interested in how to get a good combination of ‘bright side’ and ‘dark side’ behaviours. My concerns would be:

1. The ‘dark side’ behaviours you’ve provided could surely be represented as ‘bright side’ behaviours by reversing the meaning of the sentence. E.g. “Doesn’t admit when s/he has made a mistake” could be “Admits when s/he has made a mistake”.

So is it really better to have both? It runs the risk of confusing the results by having different behaviours that are difficult to compare and prioritise against each other.

2. The example ‘dark side’ behaviours are quite specific , and hint at a need to understand the root causes of why performance is weak.

Rather than using the questionnaire to get down to this level, I find it more effective to keep to 20-40 competencies that provide the whole picture, and use the qualitative feedback and the feedback review meeting to dig down into the root causes for the areas that need most improvement.

A much longer assessment can be time consuming to complete, and will often lead to less qualitative feedback. This can help to give 360s a bad impression, as people feel both that they have to spend too much time providing feedback and get too little value out of the end of the process.

I’d love to hear your thoughts (and those of other HRZone readers)!

Paddy

* l refer to an employee as well as leaders because I don’t feel 360s should be limited to leadership , though with many tools it can be time- and cost-prohibitive to extend it further!