You’re down to the final two candidates, Steady and Star, for a high-stakes job. By now they’ve been through a number of exercises which reflect a thought-through person specification. Choose Steady and there’s good evidence existing performance will be sustained but dramatic improvement is unlikely. Choose Star and the organisation could improve radically, but it could also crash and burn.

This is a familiar selection situation: what’s the right answer?

Senior roles: risk v person specification

Drilling into this question and integrating insights from research suggests that senior roles need thought-through risk appetites as well as thought-through person specifications. This shift in paradigm can open the door to better selection decisions, succession planning and diversity, and put HR in the unusual position of driving strategic conversations in the board room (see my previous article for HR Zone on HR in the boardroom).

A warning ‒ I’m talking about informed assessments emerging from a quality selection process, not lazy assumptions that (for example) an internal candidate with a dull interview manner is Steady and a flashy external candidate is Star. If you’re struggling to get colleagues over that sad (but common) hurdle, treat them to Harvard professor Joseph Bower’s excruciatingly honest six-page account of taking three goes to spot the transformative candidate for CEO lurking inside a business (pp 40-45 in his book, The CEO Within: Why Inside Outsiders Are the Key to Succession Planning).

Choosing between two equal candidates

If Steady and Star are otherwise evenly matched ‒ in other words if the range of likely outcomes from appointing each one are like two statistical distributions with the same mean but different standard deviations ‒ we sense that the right answer is situation-dependent. For example, a broadcaster who has to replace a household name as TV anchor for solemn national occasions is one selection situation; replacing the host of a ‘youth’ show which is failing to generate any buzz is quite another.

Understand your risk tolerance BEFORE selection commences

Risk appetite is a concept from investment, as your financial adviser will tell you. In investment, as in selection, nothing is zero risk. Within any class of assets (such as global oil companies’ equity or Asian banks’ debt), sometimes a fund manager should be looking for high potential, risky choices, and sometimes not: it is the investor’s risk appetite, thought through in advance, which should drive the decision. Current selection SOP (standard operating procedure) is to know your person specification in advance but not your risk appetite. That’s asking for trouble.

What is likely to go wrong if we wait until we meet Steady and Star before deciding our risk appetite?

Firstly, we may choose the wrong risk level (at senior levels, the mistake is typically adopting a risk level that is too low). Selectors for senior roles usually enjoy meeting Star during the selection process ‒ these candidates make the process more fun and their interest gratifies the selectors’ corporate ego ‒ but in the end they mostly choose Steady. Steady often has remarkably similar skills and outlook to people already in the organisation. This is like sending your financial adviser out to enjoy meeting dynamic company managements in exotic locations, but she ends up adding to your extensive stock of government bonds.

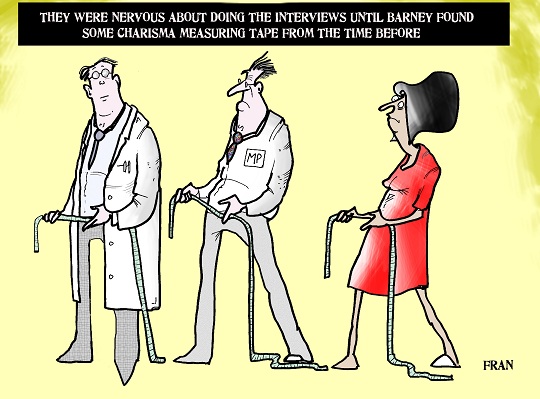

Secondly, where risks are taken, they may not be the right ones. In the absence of a strategically-driven risk appetite, ‘charisma’ has free rein. These are the occasions when your financial adviser doesn’t play safe with gilts but is over-impressed by lunch.

Thirdly, risk appetite is a portfolio concept: it can’t be considered sensibly on a stock by stock basis. Different parts of a portfolio should bear different intended risks. We need to look across the span of senior jobs in an organisation to see where selectors should be aiming for low or high risks.

And fourthly, linked to the last point, your financial adviser should not be deciding your risk appetite! Neither should individual selectors ‒ risk appetite across the span of senior jobs is a strategic board judgement.

Including risk appetite in succession plans

Twenty-first century succession planning and talent management needs boards to ask that succession plans include risk appetites as well as person specifications, with the suitability of the names put forward judged against both dimensions. Because the process will involve unfamiliar (but valuable) thought, it should be kept very simple ‒ for example allow the majority of top posts to be classified as ‘average’ risk appetite but force the identification of (say) 15% as high and 15% as low.

‘But you don’t understand. All my posts are vitally sensitive. They’ve all got to be low risk appetite!’ is a likely managerial response. To which the board’s answer should be, “think again.” To say that everything must be low risk, while technologies and business models are changing at breakneck speed, markets are turbulent and different generational attitudes are impacting the labour market, is to say you’re not a manager ‒ you’re a wishful thinker.

Assessing risk appetite using strategy and threat

Asking which top successions in your organisation should have a high risk appetite goes to the heart of debates about strategy, market opportunity and threat. It would put HR in the unfamiliar position of stimulating such discussion, not tagging along to implement. Needless to say, the board will then be able to hold managers to account on the appointments they eventually make into the high and low risk bands ‒ whether the selection decisions looked risk-appropriate at the time, and what happened afterwards.

It doesn’t directly follow that more diverse appointments (in the sense of gender, ethnicity, age etc) will be made to high risk appetite roles. However where risk appetite is not strategically driven and left to line managers gazing into Steady and Star’s eyes, selection outcomes are likely to be risk averse, with a bias towards ‘people like us’.

Of course this is bigger than diversity. Where could we imagine HR driving the boardroom agenda? It sounds a bit weird. But ‒ here’s a thought ‒ maybe in organisations where people are the most important asset?